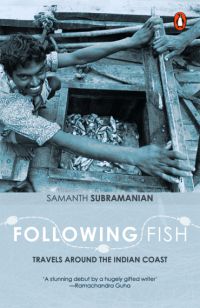

Following Fish: Travels around the Indian Coast is a fascinating collection of nine essays on the life along India's coastline by Delhi-based journalist Samanth Subramanian.

The travelogue sees Subramanian visit the nine sea shore states from West Bengal to Gujarat, exploring everything from Kerala's toddy shops to the history of an old Catholic fishing community in Tamil Nadu.

We bring you an excerpt from Chapter 2, On swallowing a live fish, where the author describes a scene at the Goud household in Hyderabad. The Gouds are known for their famous 'fish treatment' that claims to be a cure for asthama:

The Doodh Bowli section of Hyderabad, lying a couple of kilometres from the Charminar, is an ancient quarter of mosques and thin, confusing streets that regularly double back upon themselves. The Bathini Goud family's ancestral home, tucked into one of these streets, had been newly whitewashed, and its parrot-green window frames had been repainted. 'We do a pooja the day before, at the house in Doodh Bowli. It's usually just the family, but you must come,' Harinath had said, and so I had gone, curious to see the clan.

By the time Harinath and I arrived, the family was already assembled on the terrace, under a temporary canopy of cloth. In a corner, next to a small altar, the family priest sat murmuring to himself and glaring occasionally at the world at large. Harinath whipped off his shirt and sat down in the front, next to his two older brothers. I took a discreet seat at the back, feeling slightly self-conscious until I saw my fellow intruder -- a French documentary filmmaker with a digital video camera, who orbited the congregation like a diligent planet, filming the entire pooja.

Truth to tell, there wasn't much to film. This was a regular Satyanarayana pooja, performed in many Hindu homes before an occasion of significance. And like almost every one of the communal poojas I've ever attended, there were the requisite distracted children, the whimpering baby, the somber gentlemen up front, and the comforting white noise of women talking and laughing at the back. Harinath, sweating even in spite of the playful surges of monsoonal breeze that cut through the midday heat, sat very still, eyes closed, hands folded in prayer.

We must have sat there for at least an hour in this manner, and attentions began to flag. The filmmaker filmed from less bravura angles, the baby whimpered louder, Harinath sweated more, and the children, losing patience, began to make sorties downstairs into the cooler confines of the house. A little while later, some men began to bring up huge wicker baskets of cooked rice, sweets and pooris, and steel buckets of sambar and rasam. In the heat, and in the restricted confines of the canopy, the wonderful, dense smell of the food rose and hung, like a spice-seeded storm cloud, above the family. Attentions, unsurprisingly, wilted further.

Harinath finally broke a coconut, a girl came and tied a red-and-yellow thread, with a betel leaf, around the wrists of us observers, and the priest performed his arati, offering up cubes of sugar and diced bananas to the deity. It seemed like the end, but then the group moved downstairs, first to the house's stuffy pooja room and then to the real focus of all this consecration: the well.

When we'd first met, I had asked Harinath whether he had ever considered taking his treatment across India, like a traveling apothecary. He had bridled at the suggestion and then said, cryptically: 'We need our Doodh Bowli well.' Later I had persuaded him to explain that statement, and he told me about the importance of making the medicine with the water from the well in the Doodh Bowli house. 'Only that water. Nothing else will do,' he had said. One summer, he claimed, every well in Doodh Bowli had gone dry, and Hyderabad had thirsted for water -- yet the well in the ancestral home had gushed with sweet, cool water.

That well is really a small, square hole in the ground, set to one side of the courtyard past the entrance of the house. Just above it, built into the staircase leading to the terrace, is a sacred tulasi plant in a bower, as if it were benignly conferring its holy status upon the well all year round. The water is not too far below the surface, but it remains so cool that even leaning over it, during the summer months, feels like passing through a blast of air conditioning.

The priest now took position over the well and consecrated it with rice, vermillion and turmeric. As if he were a trainer pepping his boxer for the big fight, the priest flattered the well water in his recitations, calling it the embodiment of the Ganga, the Yamuna, the Narmada, the Kaveri and the Sindhu rivers. In the pooja room behind us, the women had gathered independently and were singing in low, tuneless voices. Only after that was it time to eat.

After lunch, the Bathini Goud residence was flooded with visitors -- neighbours dropping in to see how things were going, more members of the family, reporters and camera crews to interview Harinath, who seemed to have been designated communications director for the event. His daughter Alka took charge of his two cell phones, answering some calls and giving others to her father. It was, by now, past three in the afternoon, and I asked Harinath: 'But when will you actually begin making the medicine?'

'We'll probably start in the evening, or later at night, when all this has died down.'

I thought about that, and then asked: 'Can I stay to watch?'

Harinath smiled a slow, sweet smile, and said: 'You know that isn't possible.'

I knew. I'd just figured that there was no harm in trying.

Excerpted from Following Fish: Travels around the Indian Coast (Rs 250) by Samanth Subramanian, with the permission of publishers Penguin Books India.

Photograph: P Anil Kumar