Rustam Sengupta's tours to his native village in West Bengal and other remote corners of India brought him face to face with a stark reality: People in these villages have no access to electricity or clean drinking water.

After one such trip in August 2009 he decided to call it quits at an MNC bank in Singapore, where he was earning a fat salary of US $ 1,20,000 per annum (excluding commissions) as finance manager at their fixed income side and change this sorry situation.

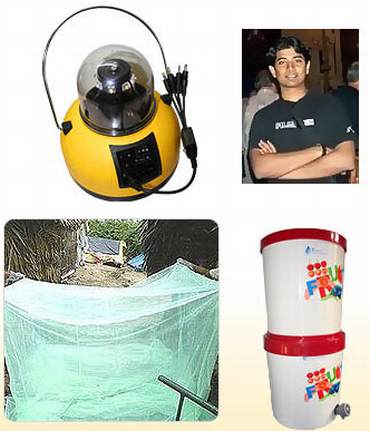

The very next month Rustam came to India and started Boond, a not-for-profit organisation, with a small team that aims to provide solar light, clean drinking water and pest control to one million people by the end of 2012.

To this end Boond sells something called the 'Boond Development Kit' consisting of a solar lamp, water filter (a 22-litre double candle ceramic water filter with two chambers separated by a ceramic membrane; advantages: roots out 90 per cent bacteria and very much suited to pond water) and mosquito net at a highly-subsidised cost with the help of distribution partners in India's remotest areas, NGOs, social investors, micro finance institutions and banks.

This is how Boond works: You buy the kits online by making a payment for the needy in some remote Indian village and Boond delivers it to them with the help of their channel partners, mostly unemployed village youth, who in turn get a three per cent commission.

Just recently, Boond succeeded in sending 90 kits to families in Ladakh that was devastated by a landslide.

"While the government and other help aid agencies offered food and built camps there was no electricity and water was contaminated leading to chronic diseases. Because of our kits, 90 families that were completely devastated have been able to jumpstart their lives," he says proudly about his team.

Ask 29-year-old Rustam, who was born and brought up in Delhi and did his masters in electrical engineering from University of California, Irvine besides an MBA from INSEAD, Singapore, why he is doing what he is doing and he explains: "I wanted to start a social enterprise that would cater to basic requirements of India's poor. I always believed in doing social work."

However, social entrepreneurship is not a bed of roses in India, he soon realised.

Rustam's contact details:

Mobile: +91 9717 349 377

E-mail: rustams@boond.net / rustams@gmail.com

Website: https://www.boond.net

....

Despite having a great working plan in place he had to face corporate apathy, law-and-order problems while working in insurgency prone remote areas of Manipur and the so-called 'Red Corridor' and the emotional drain that sets in when you see poor people fighting for basic amenities for lack of purchasing power.

While Boond has managed to earn Rs 11.5 lakh (Rs 1.05 million) in revenues till September 2010 there was a time in May this year when Rustam was absolutely bankrupt, borrowing money from whoever could lend it to fund his petrol expenses so that he could travel through Rajasthan to sell his kits that were originally meant for Manipur because of the blockade of roads by agitating Naga students.

That has not dampened his fervour though.

"You need to carry on with your idealism and faith to overcome such situations," he says.

Today, Rustam may not be earning big dollars, may not be trotting to exotic locations across South America, as he did during his stint as a consultant with Deloitte in the US, but his happiness quotient is higher than what he could have achieved in a high-flying career which he consciously chucked.

"At Standard Chartered we used to sit in front of our desk with four guys under me trying to make millions for people who were already millionaires. At Boond I am sitting with four people on a shop floor trying to package kits to be sent to remote corners of the country and trying to earn a small sum of money out of this whole exercise. Nevertheless, the satisfaction factor of being a social entrepreneur is huge and so are the challenges," he says even as he laughs heartily.

In a telephonic interview with Prasanna D Zore Rustam outlined his amazing journey from making millionaires, to going bankrupt, to striving to provide millions of poor Indians with clean water and electricity.

...

What prompted you to sacrifice a fat salary, a career that could have taken you places to start a social enterprise?

I have been quite fortunate studying at decent places, getting a scholarship to study in the US, do my MS there, work with Deloitte for a while and then go to Singapore (INSEAD) for my MBA. Whenever I came back to India I would go to my native village (in West Bengal) and other remote places in India, with my friends, and found that just because you are born in some place you are basically either advantaged or disadvantaged, which is very unfair.

What I found is that with globalisation and high economic growth happening, economic disparities too have been increasing. I always wanted to do something to change this situation.

If you go to far-flung villages in the north-east you will find gutkha being sold there. These manufacturers have built a brilliant supply chain to get to the end users even in these remote villages. But nobody uses water filters. Nobody uses unconventional source of solar lighting. If gutkha can reach remotest villages, why not water filters.

I wanted to change this sorry situation.

I found out it's important for me to give a part of my life to be really happy and satisfied into this kind of work by utilising my network, my education and my knowledge to find a middle path that will help bring about social development and economic growth in India's remote areas in a sustainable manner.

And then I started thinking about unconventional ways that do not have to depend on the governments to solve these problems in a simple way. For example, lighting, clean drinking water and pest control are key requirements of rural India for people belonging to the below poverty line category.

When I came back from one such trip, what I did was to think about the best solution, best design, to get it off the ground and also make it affordable to the target audience using some financing schemes. That's how Boond was born.

...

How do you earn money out of a social enterprise to make it sustainable?

We actually sell something called as 'Boond Development Kit'. For those who cannot afford to pay upfront we sell them through a financing partner, who pays us, and then gets paid by the buyer over a period of time.

Since the time we have started we have managed to earn Rs 11.5 lakh in revenues.

Our web site sells this kit as part of a hybrid model where you could buy a kit for somebody else. When the floods in Ladakh happened we were the first to send our kits for distribution to Ladakh through our channel partner SKITPO. While the government and other help aid agencies offered food and built camps there was no electricity and water was contaminated leading to chronic diseases.

Because of our kits 90 families that were completely devastated have been able to jumpstart their lives. We are in the process of sending some more and for that we are working out funding solutions.

What kind of challenges did you face when you started and what are the challenges you face now?

The biggest problem is that of logistics. When you want your goods, products to reach to remote places of India there is certainly no infrastructure support. Pucca roads do not connect most places; at other places the security problem is huge even though people want to take risks and reach the poor.

For example, I had been to Jharkhand but the roads to remote places are not in proper shape. In Manipur it takes more than 11 hours to walk to a remote village, where our kits are much needed, from a small town.

Also, in some places there is political/governance vacuum (the so-called Red Corridor where Maoists hold sway). We don't know how to reach these places or who to give our products to which then can be sold in those areas. Then the people are so poor in these areas that when you have shipments for 300 people there will be a huge demand for these kits but not everybody can buy because they don't have the money.

At such times handling huge crowds becomes a serious security risk apart from emotionally saddening you that there are so many poor people who still cannot avail of these kits that can give them clean light and drinking water.

...

One is tempted to ask what's the point in doing an MBA, working with an MNC bank if you always wanted to start a social enterprise?

I always knew I wanted to do something about social development and economic disparity. Going to an MBA school really gave me two good things. It taught me a lot of models that could be implemented by simply talking to my professors as well as people from outside. The other thing is it has given me a huge network of people across the globe, which effectively is being translated into support for my web site. You will not believe but 75 per cent of the Ladakh support has come from outside.

And working in Standard Chartered gave me a strong sense of how to manage things. Now I can manage my finances better and of course it gave me some money to help me tide over my gestation period.

What is the cost of the kit that you sent to Ladakh and what does it consist of?

It's Rs 2,400. You can just visit our web site and buy it and then send it to SKITPO, our partner on the ground in Ladakh. We want development to be done not just by big companies and rich people but also by ordinary people like you and me. Spending a thousand bucks or more is not too difficult for people like you and me.

These kits consists of a solar lamp, a water purifier, mosquito nets, soaps, detergents etc, things that you don't have once you are devastated.

...

Is Boond a not-for-profit organisation?

As of now we are a social enterprise but very soon we plan to become for-profit so that we can sustain our business model that endeavours to bring basic requirements to BPL category Indians at an affordable price. While taking grants will make us vulnerable to various pulls and pressures we want Boond to stand on its own feet.

What kind of profits would you need to make on an annual basis to sustain yourself?

Our agents on the ground in far-flung areas work on three per cent commission. This, while helping us sell our kits, also provides self-employment opportunities to rural youth. We are a team of five people in Delhi, who handle all the work from packaging to sending it to local distributors. While we have still not broken even we are sure that a profit fo Rs 2.5 to 3 lakh per annum can help our social enterprise sustain itself in the long term and help us set up a number of small, de-centralised service and distribution stations in lot of remote Indian villages.

Tell us about the good work that Boond has done in India till now?

I will tell you about two aspects where Boond is doing really good work. One is Boond has really managed to connect well with some of the remotest places in the North East of India, especially Manipur. Now, the North East is one of the most backward and underdeveloped regions of the country. The basic development that you and me in cities take for granted is not there.

Boond has been successful in starting a movement with the help of the local people in not only selling solar lighting and water purification kits but also developed infrastructure to service these kits, all with the help of the locals. This has helped us earn their trust.

We have reached to so remote areas where the government will take another 10 to 15 years to reach with the services we offer.

Is your happiness quotient higher as a social entrepreneur?

It's very high now as a social entrepreneur. At Standard Chartered we used to sit in front of our desk with four guys under me trying to make millions for people who were already millionaires.

At Boond I am sitting with four people in the shop floor trying to package kits to be sent to remote corners of the country and trying to earn a small sum of money out of this whole exercise. Nevertheless, the satisfaction factor is huge being a social entrepreneur and so are the challenges.

There were times when I was completely depressed about things not working out for Boond.

Did you ever feel like quitting Boond?

It never came down to me wanting to quit but there was a point in time when I had sent in my shipment and I was selling well but I wanted to expand it to the next five villages. And somehow I found that my assumption of people's philanthropic interest in India was exaggerated.

Whenever I was pitching to big corporations I found they were taking too long a time to get back. Anything to do with social aspect takes a long time to materialise. Then I was close to being bankrupt -- I was actually bankrupt for a month.

You are a single person; you come up with a lot of ideas and emotions. You think that people will catch on to your ideas and start supporting a social cause to provide light and shelter and clean drinking water to the poor and affected wholeheartedly. But you face disappointment when your expectations about people fail. Those are the real de-motivating times.

However, you need to carry on with your idealism and faith to overcome such situations. Thankfully, things are much, much better now for Boond.

...

You went almost bankrupt?

Yes, that was in May 2010. I had a great product distribution happening in Manipur and then there was this blockade by Naga students that cut all the road routes to Manipur. I tried to plead with the Naga students to let my products move to Manipur but they didn't budge.

I tried talking to the local police and the army but nobody was of much help. I couldn't help but wait for a month with my entire inventory running into huge losses. But I had to keep paying my manufacturer from my pocket. Even today I cannot ship my kits to Manipur.

Luckily I met a lot of good people who advised me to try selling these kits in Rajasthan. I took my car and travelled through the state, waiting at every village, demonstrating the importance and efficacy of my products. I managed to start on a good note but at that point I was borrowing money from friends for petrol expenses.

It was really very de-motivating and the fact that something, over which you have no control, hits you hard, makes you feel really sad.

Does being single help your social enterprise? Listen to what your heart says?

My nature is quite adventurous. I have travelled a lot through South America when I was working with Deloitte in US. But yes I am still single and it gives me a lot of flexibility. I can always take a car and start driving.

Your advice to India's young who would want to start a social enterprise?

I would just say that there would be a lot of challenges in the beginning and it is easy to get demotivated. Unfortunately, there are a huge section of people in our country, who are not very sensitive to development in remote areas. They actually do not care to watch a movement develop in the rural sector. For them materialism and consumerism is very important. This section will always try to suppress your movement.

But as a social entrepreneur you must stick to your core beliefs, ideas and business model, be very determined and headstrong and try to push it forward, all the while ignoring the naysayers.

The other thing is one must seek to collaborate with others who are into similar ventures to exchange ideas on how best you can propagate your enterprise. All these things may not happen immediately but may come with experience.