Prince Tiwari, a chartered accountant from Mumbai, could have easily landed a plum job in a multinational.

Prince Tiwari, a chartered accountant from Mumbai, could have easily landed a plum job in a multinational.

He chose instead to educate and empower the underprivileged. From 10 children in 2011, he helped 100 in 2015. This is his heart-warming story.

Photographs by Afsar Dayatar/Rediff.com

They live under the broad Western Express highway in Kandivali east, north Mumbai.

Vehicles with deafening horns ply throughout the day. The air is very dusty. There is trash everywhere.

You would, perhaps, never live here, but it is home to many families for over seven years.

A man is sitting on the uneven ground, folding clothes.

Nearby, a mother is preparing lunch on an open fire. Her sons gaze hungrily at the blackened vessel.

There is a worn out mattress on the ground. At night, a family of four sleeps here.

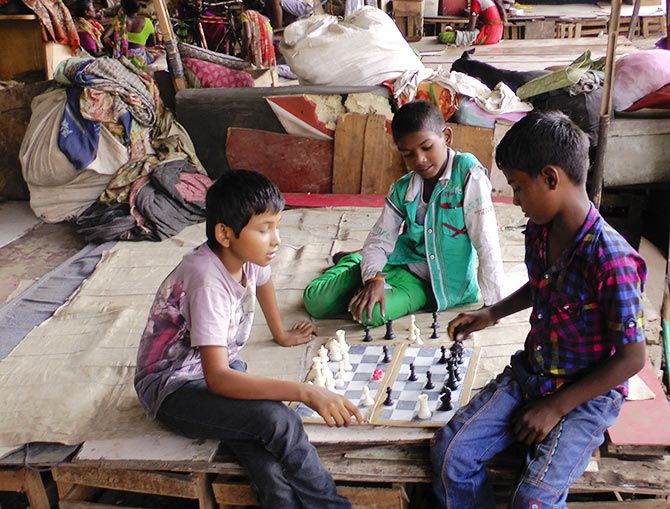

Two boys are engrossed in game of chess; a little one watches them, perhaps hoping he would join them someday.

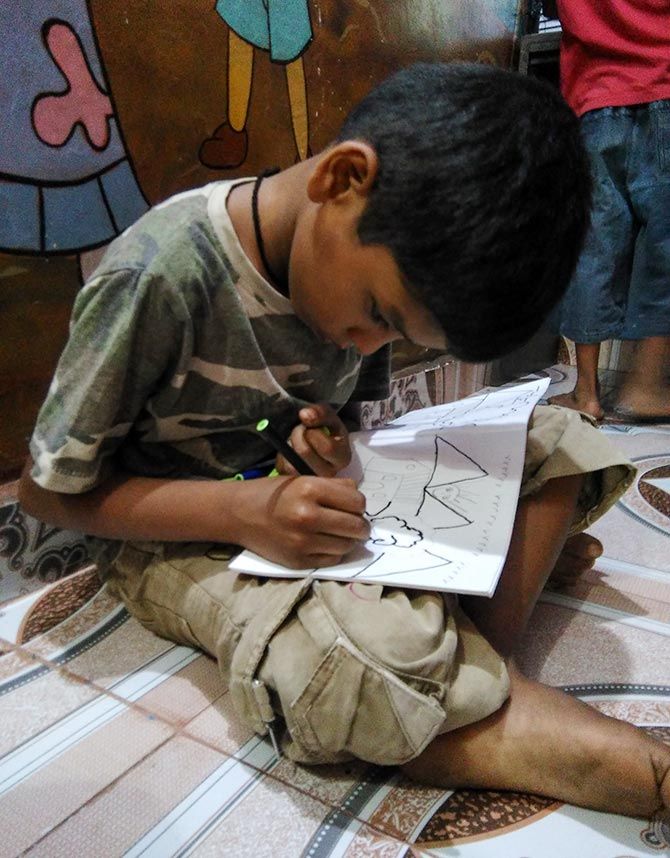

Refusing to get distracted by all this, at a slight distance, a group of children are sitting on broken benches, writing the English alphabet in their respective notebooks.

Watching their progress is a hawk-eyed young man.

Prince Tiwari (pictured below) has been educating these children, right under this flyover, since 2011.

It was only two months ago that he was able to afford a rented place where he now holds his free tutorial classes.

It is a 10 minute walk from the flyover to the house he has rented. The house has just two rooms and a few computers on a side table.

Prince points at some folding chairs. "I just got these chairs few days ago. It will be easy for the kids to study now."

The 21-year-old was a student himself when he first met these children begging for a rupee or two. Every time they caught his attention, he thanked God and his parents for the comfortable life he led.

"I am a very emotional person. I get attached to people and to things very easily. When I saw these poor and helpless children, I was upset. I wanted to do something for them," he says.

Only education, he thought, could give them a better life. One day, after college -- he was studying commerce at Thakur College in Kandivali, a north Mumbai suburb -- he quietly followed few kids begging on the streets.

They led him to the highway.

"When I met them in 2011, I was shocked to see how they live. Most people sold utensils in exchange for clothes. A few were daily wage workers. Their children went to a municipal school -- not to study, but to eat the mid-day meal," he says.

He checked their books and was horrified to see they had learnt absolutely nothing. "A girl in fourth standard didn't know to read, write or say the English alphabets," he says.

Prince was 17 years old then. He wanted to become a chartered accountant and attended a coaching class in Andheri, another Mumbai surburb. He was also interning at Deloitte as junior accountant.

"To take the final examination in college, an internship is compulsory," he says.

His college did not stress on attendance so Prince spend part of his day teaching these children.

"Initially, it was difficult to convince the kids and their parents. Though some kids were interested in studying, they didn't have anyone to guide them. A few parents said, 'Padhai karke kya karega, baad mein humare jaise hi kaam karna padega (How will studies help them; later on, they have to do what we are doing)."

Prince refused to give up.

To break the ice, he took milk and biscuits for the children daily. As they ate, he would chat with them. Gradually, they would gather at one place under the flyover.

Then, he began teaching them.

It was a struggle. Every day. But his effort began to bear fruit. After two-three months, the children began to take their studies seriously.

In his 'School on Street' -- that's what Prince calls it -- he took in children from the ages of 3 to 15 years. He would teach them from 7 to 11 am, then leave for work. On weekends, he spent the whole day teaching.

"There were only 10 to 12 kids in the beginning, but the number soon increased."

Prince taught them English, Mathematics, Science and Hindi. He provided them with notebooks, pens, pencils, erasers, rulers.

Within three years, his salary had shot up from Rs 17,700 to Rs 51,000 approximately. So he bought utensils and prepared food (like poha) for the little ones on the weekend.

By now, people in and around the area heard about him. They came forward to help with the food.

Some of his college friends stepped in to teach art and craft.

However, Prince says, he cannot forget how a few of his friends and relatives became so uncomfortable when they came to meet the children for the first time.

'Kaha baitha hain (Where are you sitting)? It's so dirty,' they'd say.

That didn't bother Prince. "I had every luxury in my life. My father is a businessman. I travelled by car and never stepped out in the heat. But when I decided to help the children, I let go all this comfort. Now, I take the train and eat with the kids and their families most of the time."

After completing his graduation and internship, he was offered jobs by Deloitte and Jindal Steel.

He turned them down.

By now, the children were a part of his life and he felt responsible for their future.

His parents, who had stood by him earlier, were unhappy. They felt he was compromising his career. They wanted him to be independent... and help the kids with the money he earned.

Prince knew that once he had a full-time job, he would not be able to help the children. "So what if I don't end up having a successful career like my friends?" he asks. "I am happy when I see my kids shine. That will be my success."

He worked on a contract basis to keep the money coming in and started looking for a place he could rent for his 'classes'.

Although he was ready to pay, housing societies were against renting a flat for street children.

And that was just the beginning of his problems.

Local corporators warned him against carrying on with his 'illegal' activities under the flyover.

"I asked them to help me find a place, but they never paid heed to my request. They could have easily provided shelter to the kids and their parents. I had no choice but to keep tutoring the children under the flyover," he says.

He wanted to put the children, who were studying in a municipal school, in a good school. Again, he ran into roadblocks.

It was difficult to get a transfer certificate from the municipal school. Prince could not provide any kind of certification himself; he was just a tutor.

It was even more difficult to find a school that was ready to admit these children even though they had improved tremendously in their studies.

'Standard match nahi kar paayega (they will not be able to meet the standard), cope nahi kar paayega peer pressure ka (they will not be able to handle the peer pressure),' he was told.

When he discussed his problem with those around him, he was told, "Aise school mein bhejne ki zarurat kya hain (what is the need to send them to such a school)? Such schools are made for other kind of children."

He was shattered. "Basic education till Class X is equal for everyone, from children of billionaires to children of those who live under a flyover. You can't deprive a child of that right," he says.

It was only last year that 24 students finally got admission in Thakur Shyamnarayan High School, an English medium school. The admission fees were Rs 7 lakhs.

Prince gave the entire amount he had saved during his three-year internship to the school. But he needed more funds.

"God was kind," he says. "A few employees from TNT India Private Limited contributed Rs 60,000 for the children."

By now, Prince was teaching 100 children. The rest went to a municipal school nearby. A few parents, he says, were against the idea of sending their children to another school.

Meanwhile, the school required the children to undergo health check-up. Most doctors in the area, says Prince, refused as they did not want to deal with 'street children'. He finally found a diagnostic centre that agreed to do the medical tests.

He also formed a non-profit organisation in 2014, Teresa, The Ocean of Humanity Foundation.

This year, 49 more children took admission in Thakur school.

"Parents could see how well their children were performing at school. Those who were against sending their kids to the new school were now keen to get them admitted there," says Prince proudly.

The people who helped them with funds in 2014 came forward and contributed Rs 30,000 this year.

Prince is also grateful to Christina Lobo from Thakur Village, who has contributed small amounts for the past three years and spread the word in and around Kandivali. Her friends and family have donated around Rs 3-4 lakhs, he says.

An NRI from the United States, Yogesh, has sent Rs 1 lakh this year.

Prince earned Rs 10,000 by selling products like paper bags and cards that the children had made during Diwali. Oracle donated of Rs 41, 500.

"We need Rs 30-35 lakhs this year. I have already raised Rs 9 lakhs from donations, but I need more. The annual fee for a child is Rs 22, 700," he says.

Prince is also planning to buy a bus for the kids to commute safely, as hiring a bus would cost him Rs 70,000 per month.

His father has given him Rs 1 lakh, which he has used as the down payment for the bus worth Rs 13 lakhs.

The children don't fail to keep their Prince bhaiyya happy. One of his students is now preparing for IIT entrance exams, while the others study regularly to get good grades.

Prince now dreams of opening a school and helping under-privileged children from different parts of the city.

"Street children should be treated like other kids," he says. "They might be poor but they are innocent. People usually think they are thieves, but I feel they are very trust-worthy. It's been five years and, till date, neither the kids nor their parents touch my belongings. I love them for their simplicity."

ALSO SEE