A journey to this Middle Eastern land turns back the page of time, discovers Vaihayasi Pande Daniel.

My teenage elder daughter at 14 has a rather distinct sense of fashion that often runs to green nail polish, Bohemian headbands, giant ear hoops, a single foot payal and hands adorned by a dozen rings.

"You will have to be a bit careful with her. That nail polish will attract attention," warned the Italian archaeologist we were sharing a taxi with as we headed across the border.

My two daughters -- the younger is 9 -- and I had just landed at the prosperous south Anatolian town of Gaziantep, from Istanbul, to start our journey into Syria. We were told that from Gaziantep numerous trains and buses could take us across the border (60 km) to our destination the ancient northern city of Aleppo (it is said to date back to 11th millennium AD).

But when the plane landed at Gaziantep -- from the air southern Anatolia was a stunningly rich, many-hued quilt of fields of pista (antep fistigi in Turkish and from where the town gets its name), olives, oranges and vineyards -- we were told that there was no longer a bus service to Syria and the only way there was by taxi for $ 45. This was communicated through a mixture of sign language, broken English and bankrupt Turkish. We were not totally certain of the cost of the whole expedition or even if we were going to eventually reach Syria.

But soon we were speeding towards Aleppo, through sparsely-populated but rolling countryside on the Turkish side of the border. At the frontier town of Kilis we were driven up to a tiny provisions store, that sold juice and detergents among other stuff. At this store, over a cup of chai, it was explained to us that a second taxi would take us across the border and to Aleppo for another $ 60.

Zekeriye Guven, our Turkish taxi driver, soon drove up in a peppy black Opel and cheerfully loaded us in. We were then joined by the elderly woman archaeologist, who was catching a ride with us. She was headed to a dig that was happening in a little village outside Aleppo (she said she often divided time between Syria and Italy).

As we drew closer to the border the oncoming traffic consisted mainly of giant trailer tractors carrying large orders of pickup trucks headed for Iraq (hostilities had redrawn the shortest route to Iraq to make it run via Turkey, though Syria and Iraq shared a border).

We had our first glimpse of the red-white-black Syrian tricolour 20 minutes later, as we pulled up at the Turkish-Syrian border control. The Turks stamped our passports and sent us to the Syrian officers. Cheerful confusion reigned here and there was a bit of a slowdown when I mentioned I was a journalist -- the Italian archaeologist groaned: "You should have said you are a housewife. Now you will be followed!" -- but in about half an hour they stamped our passports and sent us on our way.

Forty five minutes later rolled into lively, chaotic Aleppo. The archaeologist bid us good bye at the famous Baron's Hotel where she was put up (before her Teddy Roosevelt, Lawrence of Arabia, Kemal Ataturk, Agatha Christie, Freya Stark, Charles Lindbergh, Yuri Gagarin had stayed at this gracious hotel). After a checking in at the slightly scruffy but friendly Al Faisal Hotel nearby we hit the streets at 9 pm looking for a rather rare commodity -- a vegetarian dinner.

We were directed to a Falafal fast food stall. The moment my daughters and I entered the stall business just froze. Everyone stopped eating and talking and turned around to have a good look at us. I shuffled embarrassedly through my Turkish liras, wondering how I was going to buy a meal when the owner graciously beckoned, "Indian! Welcome. I will give you dinner. Don't want money."

We were soon armed with three cones of takeaway Falafals -- delicious, freshly-fried lentil balls stuffed in rolls of fragrant pita with lettuce, onion and tomatoes, that unknown to us was dripping giant gobs of white tahini on the toes of our shoes (there's an art to eating a Syrian Falafel). As we walked down the streets of this old-fashioned town -- as the Italian archaeologist had promised -- my green finger-nailed daughter attracted bucket-loads of curiosity.

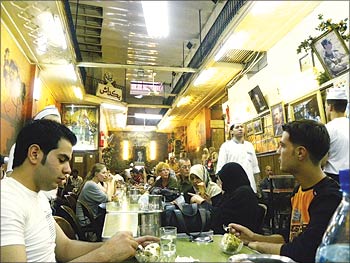

Women were hardly visible, probably because it was late. The few that were, accompanying their husbands, were demurely clothed, heads covered (no lovey-dovey gestures between couples around here). And men -- young and old -- often stopped in their tracks, mouths gaping, to harmlessly get a good look at my daughter. Cafes and restaurants were full of chatting, laughing men, playing backgammon hidden behind wreaths of smoke -- but no women. And when we sat down at the central square to observe the nightlife, a group of young men came across and generously offered my daughter a cigarette to her astonishment and amusement.Image: Like the Lebanese, the Turks and other Middle Easterners, the Syrians like their desserts extra sweet, gooey with treacle or honey and packed with cream and/or nuts and fruits. Damascene confectioners have a formidable reputation. Special favourites are Baklava, Qatayif, Pistache de Alep and Mabroomeh

Everywhere folks were equally curious about our nationality. Our answer inevitably elicited happiness and amazement. "Welcome, welcome," was always the warm, affectionate response. But Syria is quite obviously rather familiar with India. All the main theatres in Damascus and Aleppo's new town were playing Hindi films. Albeit pretty dated ones, like Army. Posters of Shah Rukh Khan, Sridevi, Bobby Deol and Priyanka Chopra were up.

Journeying to Syria from progressive Turkey brings into sharp focus the legacy of Turkey's first president Mustafa Kemal Ataturk who was determined that his country would be strongly secular, democratic and always modern-looking. Quite literally the difference between Syria and Turkey is Ataturk. Just 60 kilometres out of Gaziantep and you are once again entering the Third World.

Smooth roads give way to bumpier ones. Litter appears on the horizon and buildings, petrol stations have a run-down, shabby look (but petrol is much cheaper in Syria the taxi man informed us). Traffic has a chaotic pattern and a variety of strange three-wheeled vehicles make their appearance. Although women can be seen working in the fields and helping with sheep they are generally more in the background.

The modern buildings have dead-boring Communist cement block style to them. Policemen are all over the place. Pictures of Syria's secular Ba'athist President Bashar al-Assad gaze benignly down at you from every building and store -- a standard symbol of a personality cult fostered in an authoritarian state. Assad, an ophthalmologist who was trained in London, inherited the presidency from his father, the tyrannical Hafez al-Assad and hails from the western Syrian Alawite Shia minority (incidentally doctors seem to abound in this country and they are all super-specialists; every street corner has a clinic of a cancer haematologist or an orthopaedic traumatologist, whatever that may be).

Under Bashar's rule, the country is slowly opening out and blossoming. But tourists are still few. If you go to the State Department site the lengthy warnings will give you an idea why: Syria is included on the Department of State's List of State Sponsors of Terrorism

But as Indians we had no reason to be nervous. In fact I am always quite surprised how warm people are towards you the moment they discover you are from India, wherever I go. Their faces immediately light up and they acknowledge you with great reverence. And in spite of the State Department there is nothing in the least bit sinister about Syria -- it is an energetic, lively place, full of the Eastern hospitality that we Indians crave. People are kind-hearted, helpful, affectionate towards children and tourists are rare enough to prompt a warm welcome.

Enter Syria and you are entering a strongly Arab country. The Latin script, that Ataturk forced the Turkish language to be written in, gives way to only Arabic. Many locals cannot read anything written in the Latin script which often makes communicating difficult because even an address must be written in Arabic. It is not your imagination -- muezzin calls are much louder in Syria than Turkey.

For the very same reasons a journey into Syria has a strange but rather charming retro feel -- a feeling of slipping a few decades backwards, into maybe the 1950s (as it once was to go from Mumbai to Kolkata). As journalist Robert Kaplan put it: travelling from Turkey to Syria is like going from a Technicolor photograph in a black and white daguerreotype.

Unfortunately we arrived on a Thursday night in Aleppo. Friday is a major holiday in Syria. Nothing was open the next morning. Not the souk. Nor a travel agent. Or any store. The streets were a bit deserted and quiet, except for the service that was taking place in a Syrian Christian church. Ten percent of Syrians are Christian. Very old strains of Christianity have been practiced in Syria continuously for centuries. Incidentally, there's an Indian connection -- India's Syrian Christian sect is a part of the Syriac Orthodox church.

We opted for a fast train to the capital Damascus instead. First class trains are spiffy enough, by Indian standards -- air-conditioned chair cars with picture, plate-glass windows.

A journey from Aleppo to Damascus (two of Syria's largest cities) is a journey from the northern more-Ottoman influenced Syria, that supports an interestingly diverse population of Kurds, Armenians, Maronites and Syriac Christians, Syrian Turkmen to the Sunni-dominated central Syria (Syria is 85 per cent Sunni Muslim). Image: Damascus's Umayyed mosque was once both a church and a temple at the same time until the caliph bought it over and built a mosque patterned on the shrine at Medina

First we were journeying through some of the same gloriously fertile countryside we saw on our way into Aleppo. Afterwards it was large expanses of desert, scrubland and Syria's snow-capped coastal mountains. Bedouins, with their checked head scarves herding giant flocks of sheep, were a permanent feature on the horizon. Their temporary settlements consisted of a circle of tents, a few donkeys, the sheep and always a pick up truck.

Damascus was a bit more modern and less sleepy than Aleppo. There were many more 'liberated' (scarf-less) women; green nail polish attracted less curiosity. But the city has that Moscow-or-it-could be-Bucharest-or-Sofia-in-the-1980s-look. It is also very much a city on the crossroads, neither totally eastern, nor western, not really completely modern, part decrepit, part Christian, part Arab, mildly attractive, with a tumultuous history. In the last 200 hundred years it has been ruled both by the Turks and the French and in the 6,800 years before that by Mongols, Romans, Persians, Egyptians you name it.

Its imposing Ummayed mosque is one of the oldest mosques in the world, built around 715 AD at the site of church that was once a Roman temple to Jupiter. The head of John the Baptist is buried here, a testimony to Syria's rich tapestry of religions.

The city seems to be growing fast, edging into the dry, dusty desert. At the same time it is gaining a young, fashionable caf culture with interesting restaurants and bustling shops. Like the rest of Syria it is a smoker's paradise. Hookahs abound. Syrians smoke incessantly. Your waiter, the ice cream man, the taxi drivers all puff away.Image: Ice cream, non-stop, at the 100-year-old Bakdash ice cream parlour at Damascus' main souk. This parlour, where fluffy, mountains of ice cream are pounded by hand with cricket-bat shaped mallets, has been serving ice cream from the Ottoman times! The ice cream cone is also said to have originated in Syria using Zalabia batter; by the way Zalabia is basically a Jalebi

Like the Turkish pazars, Syrian souks are addictive. In both Damascus and Aleppo the souks were located in the older quarter of the city conveniently close to the main mosque. Both Aleppo and Damascus are considered two of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.

Dip into the souk and you have instant relief from the hot Syrian sun. Damascus' souk has high airy ceilings and wide avenues; Aleppo's souk is built from thick brick quite like shopping in the catacombs of a wine cellar.

Fresh mulberry juice stalls dot the souks. And vendors come around wheeling hard-boiled candy. The souks are packed out and the locals do their regular shopping out here. Different areas of the bazaar specialized in different wares -- colourful heaps of mysterious spices, sugared almonds, sweets, traditional medicines made from animal parts. Syria's best bargains -- frightfully reasonable -- are extra fine silk scarves, wooden mosaic with pearl inlay trays/boxes, silver and gold jewellery embossed with Syriac designs, gaudy gold embroidered tablecloths, wool carpets and delicate hand-blown glass. The Syrian pound goes a long way!

'But most of the stuff being hawked in Syrian markets is way over the top. We had to give most of the footwear a miss -- jazzy, sequined, Bollywood-Dreams-ish sandals are the norm. Tastes are kitschy and showy. Quite obviously Syrian women, under their solemn black robes, prefer some rather hot numbers crafted from fluffy gauze, roses, lace and in a rainbow of colours. Lingerie, sold in special shops, was equally risqu -- a variety of scrumptious-looking lacy confetti that would need a manual to help decipher its usage (or undoing).

At Aleppo's souk interestingly a pack of gypsies came roaming through. Their features and flamboyant style of dress was strikingly different from the locals. Syria, particularly Aleppo, apparently has a large floating population of gypsies that trace their ancestry to Europe and to India. In fact, one of the languages of Syria is Domari, which some of Syria's gypsy groups speak. Domari is also spoken in India.