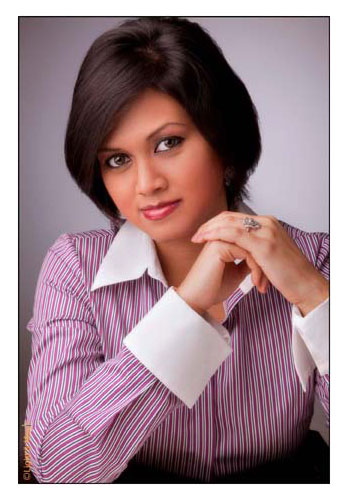

CEO of VU Technologies and executive director of Zenith, Devita Saraf (27) does not pretend to be a poor little rich girl. After all, she is running the second largest PC manufacturing business in India, and she has no qualms when she says she 'doesn't need to be simple'.

Saraf has a personal publicist who tells us that she loves Prada, Burberry and Dior and that she wears MaxMara and Karen Millen to work. The publicist also mentions that she travels quite a bit and 'has been doing so at least twice a month since 1999'.

When we visit Saraf's office in Mumbai, her designer sleeves are rolled up. She's in the midst of launching a new product but is unhappy with the way it looks. An IIT grad is waiting upon her as the two discuss the finer details about a video conferencing gadget that sits on her side table.

Saraf's handshake is firm, quite like her views about running the company. At 27, she is in the business of making televisions -- intelligent screens that will address the various needs of today's generation -- and she seems well aware of what's what and what's not.

Saraf, quite like the Biyani scions, was placed somewhere at the top by her father Raj Saraf, who launched Zenith in pre-liberalised India. At 22, she was made an executive director and found herself making decisions that were far beyond the perceptions of an average 20-something. It wasn't anything Saraf had resented. On the contrary, it was exactly what she was looking forward to.

"I wanted to be part of Zenith for as long as I remember," she says. "My brother and I would often visit factory openings and press conferences. I was always aware that this is where I would eventually be."

The grooming, in that sense, had started a long time ago. She says she's been visiting the Zenith office ever since she was 16 -- 'at times bunking college and on one occasion an examination too' -- and dreaming of making a difference in a business that her father started.

After finishing her first two years of junior college in Mumbai, Saraf went off to the University of Southern California where she obtained her bachelors in business administration with a specialisation in marketing. She also boasts of a course in Game Theory and Strategic Thinking from the London School of Economics.

When you ask her about her schooling though, she sounds somewhat acidic. She tells you that education in India is not something she's really fond of and hence went abroad at the first given occasion.

"They want to categorise you, which I always resented. I was not a topper in school and hated mathematics like most kids. But I did become part of Mensa (an international society of people whose IQ ranks in the top 2 per cent of the world's population)," she says.

When Saraf returned to India, she knew there was a chair waiting for her at the Zenith office. She insists, though, that taking up that offer was a choice she consciously made and was not something that was imposed upon her.

Getting into a world dominated by men and making gadgets that would be used largely by them was a challenge. But then again, she was in the business that targeted young professionals -- as young or slightly older than she was then, 22.

Even as her age gave her the unique advantage of understanding the needs of the target audience, as a woman Saraf found herself in a somewhat envious position. "Men fall in love with gadgets. As a woman, I don't, so it gives me the perspective of understanding what is lacking in my product," she says.

Saraf occupies one of three cabins on the first floor of Zenith's office building in Mumbai. The other two belong to her father and her brother. The majority of the company's workforce occupies the space below.

Not having worked bottom-up doesn't bother this 27-year-old at all. She says it is a practice that is followed in 'industries where there are a lot of blue-collared labourers to be appeased when the owner's child is introduced to the business'. "In a software firm, people as young as 25 are in responsible positions and most understand that age does not really matter much," she says.

Yet, she knew she would have to face some resentment when she joined the company, more so from folks who have been working with her father for decades. She also knew she had to work her way around it.

"Instead of barging in, I tried to ease my way into the company. I got myself introduced to teams and their leaders and tried to understand their functioning and dynamics."

This, she says has been her biggest challenge, something she's been trying to work around since the time she's joined.

Saraf feels understanding employee equations is the best way one can harness their true potential. For this, she too has had to change herself and her ways of functioning. Her recent peer-review feedback marked her very low on her listening skills, a fact she hadn't realised till she was reading those reports.

"I have always believed in getting feedback from my team. It helps me understand where I am going wrong and change myself accordingly," she says.

Yet, Saraf is selective when it comes to taking advice. She tells us that she consciously shuts herself off from 'talks about me'. From behind the glass walls of her office, she points to a corner where her subordinates gather for their chai and cigarette breaks. She says, "I know what they say about me behind my back. But I cannot afford to be affected by everything everyone says. Of course, feedback is one of the most important aspects of running a team, but there are times when you have to take it with a pinch of salt. Office gossip is something I prefer to stay away from."

Close to the chai stall, Zenith is constructing a new office space -- presumably larger and swankier. This is where Saraf and her colleagues are about to move soon. Surely, there are larger issues to be addressed: like recovering from the economic slowdown, for instance.

Saraf, though, claims that the downturn months were some of the best for her. "You could buy property to expand your business and employees were not throwing attitude," she says.

In one of her WSJ columns, she writes somewhat pointedly about these issues: 'I can pay real salaries, instead of kow-towing to the whims of young whipper-snappers who conveniently add a few zeros to the salary they deserve. I get real prices from my own suppliers and they stick to deadlines because they appreciate the business they have. It's just the rudest wake-up call we've ever had.'

She claims that during the downturn, she never had to let anyone go because of cost cutting. "If we'd let off someone, it was because they had integrity issues," she insists "And that is something we do not tolerate at Zenith."

When you ask her if she makes any efforts to retain her outgoing talent, Saraf takes you by surprise. "If someone wants to go, I ask them to leave at the end of that very day and get a replacement. My experience has been that the replacement is better than the older one. No one should think they are indispensable," she says with an alarming candidness. "If, however, my employees need time to get some things sorted in their life, I let them have it. I also offer to help. But if someone's made up their mind, I see little point in keeping them back."

So what kind of people does Devita Saraf hire? "Someone who does not need to be spoon-fed, can take initiatives and can make decisions independent of me," she says, adding that during a job interview, 'it's the handshake that is the clincher'.

Which brings us to a question about whether she is really able to let go of some control, a trait not many bosses of family businesses can boast of. "Not entirely," she smiles. "While I have people looking after certain aspects of the business, I have to take the final call. Like this prototype that sits behind you needs more grey on the webcam, because there's more grey..." she trails off, before you ask her if she's being a control freak.

Pat comes the reply, "No! I like paying attention to detail."

Saraf tells us that she's sobered down over the years and has learned to take things a little easier. She says: "I have been told that it'll hold me in good stead. Also, over the years I have come to realise that change comes only eventually. There is a reason why things are working in a certain way and you've got to understand the working before shaking things up."

In her voice, though, you sense restlessness, something that comes across in one of her columns where she compares herself with Simba, the lion cub from Disney's animation blockbuster Lion King, who is about to inherit his father's empire. She imagines him thinking: 'Oh boy, looks like an operational nightmare'.

But as a young Turk in a family business, Devita Saraf understands that impatience will take her nowhere. And there is a reason why her father occupies a much larger cabin than her own.

One of her later columns finds her in a subdued mood. She writes: 'We may feel that our parents aren't clued in, and they usually are not. But we cannot deny that they have seen more difficult days and their concern is justified But the cautiousness of a generation above us, who has seen the country through its dimmer days, is needed to guide us through the choppy waters of the current economic environment.'

Outside the office you spot an employee hovering with some papers in hand. Saraf will need to see these and discuss them with her brother who is not in his office yet and her father, who has just walked in. Then there is a long flight to the US where she will attend a tech exhibition, address a gathering at her alma mater and pay a visit to her US office. Work needs to be done and decisions need to be taken. Whoever said being 27 was easy?