Photographs: Courtesy Moloy Ghosh Priyanka

Recovering from a severe illness and left with no choice, Moloy Ghosh turned to digitising old records for a living. As he makes his living doing just that, Ghosh is faced with the scary prospect -- what happens when there are no records left to be digitised?

A cursory look at the LP records collection at the Ghosh household and one would point out that it includes compositions of classical music of the early 1920s or later, of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ustad Mohammad Hussain Khan, Ustad Faiz Khan, Bismillah Khan, Professor Jnanendra Prasad Goswami, Abdul Karim Khan, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

It also includes LPs of the pre-Independence times when Begham Akhtar was known as Akhtari Bai, and when Bhimsen Joshi released his compositions as a 39 year-old.

These and many more LPs are neatly stacked in Moloy Ghosh's room.

His job is to convert rare LPs into new age music format. When his clients come to collect his music collection, Ghosh will deliver it to him preferably in a CD, with the promise that the background hissing sound in a LP would be noticeably reduced.

This is what Ghosh does for a living from his apartment in New Delhi's Indirapuram area.

Ghosh spent his childhood and schooling years in Kolkata growing up to devotional songs in their house. The music around him led him to pick up Rabindra Sangeet when he was quite young -- four years old, if you are to believe him.

While the young Ghosh was learning music at home and in classes, after he had completed class 12th, something else was happening alongside.

The Ghosh family and their neighbours next door did not get along, and hence, just to spite the family, their neighbour would play the radio rather loudly all day long.

"My ears have been listening to music since I was a child," says Ghosh.

In fact, he had become so accustomed to the music from the neighbours next door, that he would come home from school, eager to listen to it! His mind would wander off to what played next door even when he was in the midst of mathematics equations!

He distinctly remembers the programmes he used to listen to on Vividh Bharati. "I used to wait for Chaya Geet and Hawa Mahal on the radio." In course of time, he had not only become well versed with the names of Hindi music compositors and singers, he says that he had developed an ear for sur and taal.

"I now think I am most grateful to my neighbour. Those were my first lessons," Ghosh laughs in retrospect.

The initial days of joy from music faded as he completed school and was packed off to study engineering. He worked briefly and later pursued a degree in management.

His education in music would however remain informal while he was in college. Ghosh now recalls that he would often sing in college, mostly on the request of his seniors and in order to dodge ragging. And while singing and music stayed on with him, his grades in college gradually fell.

Ghosh also had begun to experience physical tiredness in his hands and arms, and was unable to write for long periods of time at one go. He consulted many doctors at Manipal, where he was studying.

"I just could not write for long," Ghosh begins to explain. "During exams, I used to rest my arm for half the duration of the paper. I used to fare badly in subjective papers," he says. His parents took him to neurologists. The visits to doctors were inconclusive, many of them cited psychological reasons suggesting that he was tensed and stressed out.

Ghosh however observed that he was increasingly becoming incapable of writing. Even though he scored well in objective-type papers, in the subjective ones he scored terribly.

You can't but help feel a sense of sympathy for Ghosh as he says, "I used to write on the answer sheets in red sketch pen that I was suffering from a condition that makes my handwriting poor, begging my examiners to consider my problem."

Sadly, Ghosh would never know what the condition was till years later.

Meanwhile he plodded first through college and then through his work life.

"I was into marketing (before I quit) and I used to find it very difficult to write reports manually. For the first few years, it was exceptionally tough," he says.

To make matters worse he found it difficult to comprehend multiple instructions -- a problem that persists to this day. In a marketing job that demanded results every single day, Ghosh was clearly at a disadvantage.

"I sometimes find it difficult to follow so many things people say at once on the phone. I have to really pay attention," he explains.

Music stayed close to him during all these years. He was singing at informal functions, but he still didn't see it as an alternate mode of earning, a way out from a dreary job that tired him beyond measure. Music was just there for him, he says.

Ghosh was married during this time to Chandrani who holds a master's degree in classical music from the University of Delhi.

"I always wanted my wife to understand my passion for music."

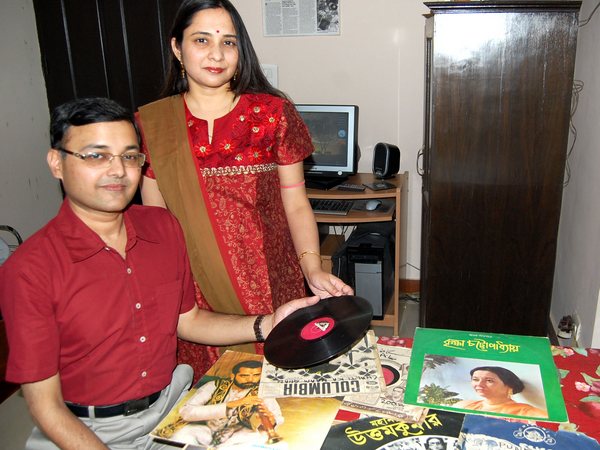

Moloy Ghosh preserves musical gems for the next generation

Image: Wife Chandrani holds a Master's degree in Music and has been one of Moloy Ghosh's greatest supportPhotographs: Courtesy Moloy Ghosh

By 2008, Ghosh was working in marketing for a decade now but had changed several jobs

The same year, tragedy struck. Moloy Ghosh his mother to cancer. Additionally, he was diagnosed with Hepatitis-B the same year and had to remain in hospital for over six months.

"Those were the most difficult and hard times of my life," Ghosh says pensively, "That year made me rethink many aspects of life."

Meanwhile, the doctors had told him that there was no way he could continue with the job he held at the time.

"That year was life shattering," he says. "I didn't know how life would go on and what job to take up," he says.

It was around the time that a DVD of Taare Zameen Par made its way to him quite by chance.

"As I sat watching the film, I realised I had similar issues that the boy (the film's protagonist) suffered from. I figured I had a form of dyslexia."

Ghosh says he has dysgraphia, something he figured by reading up after watching the movie but curiously he never got himself tested for it or sought further medical help to be able to find his way around the condition.

In any case, by the time he had recovered from Hepatits he was quite sure he didn't want to return to his old job. He was looking for newer avenues.

At first Ghosh joined a call centre but quit soon after on medical advice. Lost and confused, it was his wife who suggested that he try his hand at something in music.

"She was the one who put the idea in my head," he says. "I have always been passionate about music and so is she. So we started exploring possibilities."

At first he toyed with the idea of teaching music. "Ghaziabad is an up and coming locality and I used to see a lot of Bengali families in the area so I thought I could possibly teach young children Rabindra Sangeet."

However, something else happened in the meanwhile.

"I was trying to get some of my records of (the Bengali singer) Krishna Chatterjee digitised. (After I put a word out there) Someone from Mumbai called back and asked me to send across the records," he recollects. "There was no way I was going to send them to Mumbai. What if they got lost or broken on the way?"

So, just like that he hit upon the idea! Ghosh then went over to his father-in-law, a former Defence Research & Development Organisation officer, borrowed an old record player from him and started working on it. A year later, he purchased a new record player from London for Rs 16,000 and additional software from the US worth Rs 5000.

"It was very hard putting the money together. I was out of work and had very little money," he says.

"Digitising LPs is not everything," Ghosh begins to explain, adding that the process of digitising has almost become automatic now, especially with the newer available equipment.

Perhaps Ghosh's expertise lies in the process where he is able to suppress the hissing sound in a LP, which is very prominent.

He had to work for months initially on the software that he had bought. His work would enhance the audio quality when a composition is put on a compact disc; it would reduce the background hissing sound and make the music sharper.

"Both my wife and I would spent months, initially, listening in to each and every voice and note," he says.

"Now, my ears are trained at picking up voices and notes," he says.

He preserves musical gems for the next generation

Image: Some of the record covers that Moloy Ghosh has converted into a digitised formatPhotographs: Courtesy Moloy Ghosh

Ghosh works out of his home in Delhi where he's converted one of the rooms into a studio of sorts. It contains, among other things, record players, LPs and even a few rare 78 RPM recordings. He keeps most of these packed away as they are fragile and need to be preserved.

As with any new business, the initial days were very difficult for them as well. They didn't have a budget to market about the new job.

So he and his wife began making posters and pamphlets. They started with a few mithai shops in Chittaranjan Park, a prominent Bengali locality in the capital and persuaded the shopkeepers to let them display the posters at the shops.

For the next few months, Ghosh and his wife would take out printouts and post them in and around local shops. A few people did call. An old colleague of his father and the father of one of his friends were his first clients.

The business gradually started to gain ground around December 2009.

Ghosh now gets 10-12 clients each month. He charges Rs 350 to convert an LP of Hindi classical music into a new-age format of music and says he makes just enough to run the house.

Most of his clients are private individuals -- barring one particular person who gave him an order to convert 100 LPs -- but he's hoping he'll land a contract to digitise a library "or even a part of it."

"It would cover me for a few months," he says.

The oldest LP he has ever had to work on belonged to compositions by Khan Saheb Abdul Karim Khan, who died in 1937.

And it's not just the old classical music. Ghosh would proudly say that he has worked on a few Western classical LPs as well. These included Austrian symphony Orchestra, Azatullah-Saraiki, Brahms Piano Concerto No 02, Brahms Symphony in C Minor,Daniel Barenboim, majority of Jim Reeves LPs, Pepe Jaramillo -- Mexico Tropicale, The Best Of Bert Kaempfert, some rare instrumentals like Paul Mauriat plays Beatles, Geoff Love and his orchestra.

"People who come here really treasure their LPs, mostly handed over by older generations. They want to preserve it," Ghosh says, "The greatest joy is to see them happy. They know the music is now preserved, it is in a CD and with better sound quality."

Even so, work (and thereby income) is erratic. There are months when he is neck deep in work, and then there are other months when it is hard to come by. This worries him.

Also, there is also the problem that the business of restoring LPs, EPs will not be around forever.

"There will be a time when there won't be any LPs left to be converted. What do I do then?" he asks.

That is perhaps the biggest irony of his job -- the harder he works, the greater are the chances he'll run out of business.

"Perhaps I could do some work in the field of audio restorations," he says as his voice trails off.

Till then Moloy Ghosh must look to the past, place a record on the turntable and work to its tune.

Moloy Ghosh can be contacted at nutanjauban@gmail.com

Comment

article