Mihir Patkar, ThinkDigit.com

It seems that everyone is talking about 3D television these days. A few friends and relatives who called up for advice regarding what TV to buy even asked if they should wait till next year to get a 3D TV. Given the recent interest, we thought it would be appropriate to give a brief explanation of the mechanics behind stereoscopy -- any technique that creates the illusion of depth of three-dimensionality in an image.

There is one basic preface needed in understanding 3D television: understanding how our eyes work. For the sake of this example, look at your computer mouse (or if you're on a laptop, any other object nearby).

In a nutshell, your left eye and your right eye are two separate lenses, registering two differently-angled images of the mouse, which are then sent to your brain.

The brain then acts as the 'image processor', putting the two pictures together to come up with one three-dimensional picture in your mind. It's basically the same principle by which the new FujiFilm FinePix 3D camera works.

Making screens display 3D images is based on a similar mechanism, but is divided into two main wings: Stereoscopic TVs (which require special glasses to watch 3D movies) and Autostereoscopic TVs (which appear 3D without any special accessories like glasses).

Let's look at special glasses that are required by some of the upcoming stereoscopic TVs to deliver the 3D experience.

...

Check out: The all new Gadgets and Gaming page!

Reader invite

Are you a gadget/gaming wizard/afficianado? Would you like to write on gadgets, gaming, the Internet, software technologies, OSs and the works for us? Send us a sample of your writing to getahead@rediff.com with the subject as 'I'm a tech wizard/afficianado' and we will get in touch with you.

Image courtesy: 3d-forums, Sharp, HowStuffWorks, Philips, Columbia Pictures, Tridelity

Shutter glasses

The 3D technology that Panasonic, Sony and Nvidia are most gung-ho about in the near future is based on wearing what are called 'shutter glasses'. Basically, these are glasses that alternately shut off the left eye and right eye, while the TV emits separate images meant for each eye, thus creating a 3D image in the viewer's mind.

Here's how it works

The video signal of the TV stores an image meant for the left eye on its even field, and an image meant for the right eye on its odd field. The TV itself is synchronised with the shutter glasses via infra-red or RF technology.

The shutter glasses contain liquid crystal and a polarising filter. Upon receiving the appropriately synced signal from the TV, the shutter glass is automatically applied with a slight current that makes it dark, as if a shutter was drawn (hence the name). So at a time, only one eye is seeing one image.

The technology perfectly draws the shutters over either eye to make the left eye see the image meant for it on the even field, and make the right eye see the odd field of the video signal. By viewing these two images from different orientations, a 3D image is built up by the viewer's brain.

While it seems like this would cause a delay for the viewer, there's no need for such worries. With the high screen refresh rates that these modern 3D televisions have, the end user's viewing experience is seamless, smooth and rich.

However, the one downside of this technology is that due to the rapid drawing of 'shutters', lesser light reaches the eye, thus making the image seem darker than it is.

...

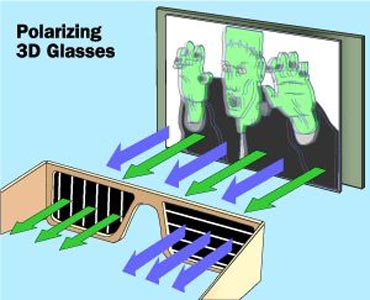

Polarised glasses

Polarised glasses are basically your regular sunglasses, and have been used as a medium for 3D stereoscopic viewing for a long time now. They are also the most popular mode of 3D glasses, currently used by large cinema houses and IMAX. Just like the shutter glasses, polarised glasses use the lenses to show different images to each eye, making the brain construct a 3D image for the viewer.

Here's how it works

For polarised glasses to work, the movie being shown has to be shot using either two cameras, or a single camera with two lenses. Two projectors (left and right), both fitted with polarising filters on their lenses, then simultaneously show the movie on the same screen. The polarising filter orients images from the left projector to one plane (for the sake of example, let's say 'vertical'); and the filter on the right lens orients its images to the plane that is perpendicular to the left one ('horizontal').

The viewer sits wearing the special glasses, which are equipped with differently polarised lenses. The left lens of the glasses is aligned with the same plane (vertical) that the left projector is throwing up images at; and the right lens is aligned perpendicularly to correspond with the plane of the right projector (horizontal).

Thus, the viewer's left eye sees only the images which the left projector is screening, while the viewer's right eye sees only the images which the right projector is screening. As both the images are taken from different angles, the viewer's brain combines the two to come up with a single 3D image.

But again, like the shutter glasses, the amount of light reaching your eyes with polarised glasses is significantly lesser, making the image appear darker than it is.

Summing up

The biggest disadvantage with stereoscopic 3D TV is that it requires the user to wear a special apparatus. This is quite inconvenient and a burden, as it renders a large screen obsolete without a pair of tiny glasses; that is, if you aren't wearing the shutter or polarised glasses, the images on the screen will appear distorted.

So what's the alternative?

Click NEXT to read about the technology behind next-gen television sets that don't require the viewers to wear glasses or any special apparatus at all.

Note: Some curious readers might want to know what happened to the red-and-blue anaglyph 3D glasses of old. Well, apart from making a lot of viewers nauseous, that technique was dependent on the studio using special colour filters while recording movies. The entire process was not worth the time, money and effort for the studios, so the technology is pretty much obsolete now, as far as mainstream video content is concerned.

How 3D TV works: Without glasses

In the previous three slides you read about the different ways in which 3D television works when paired with special glasses. However, this stereoscopic method leads to two distinctive problems:

1) The glasses are really cumbersome and expensive, and you don't want to accidentally sit on one or lose it. Plus, it takes away the simplicity of television as it stands today, where you simply hit the remote and start watching.

2) Also, without the glasses, any 3D content is completely unusable. The screen has been calibrated to work with 3D content and so dropping the glasses would end up displaying garbled images.

Recognising these limitations, several companies like LG and Panasonic are working on making autostereoscopic 3D TVs, where the user is free of any special accessories.

But before going on, here's a recap of the one basic preface needed in understanding 3D television: understanding how our eyes work.

For the sake of this example, look at your computer mouse (or if you're on a laptop, any other three-dimensional object nearby).

In a nutshell, your left eye and your right eye are two separate lenses, registering two different angles of the mouse. The two eyes send the two differently-angled images of the mouse to your brain. The brain then acts as the 'image processor', putting the two pictures together to come up with one three-dimensional picture in your mind. It's basically the same principle by which the new FujiFilm FinePix 3D camera works.

Autostereoscopic 3D television sets work on a similar principle, with two main technologies that rely on it: lenticular lenses and parallax barrier.

...

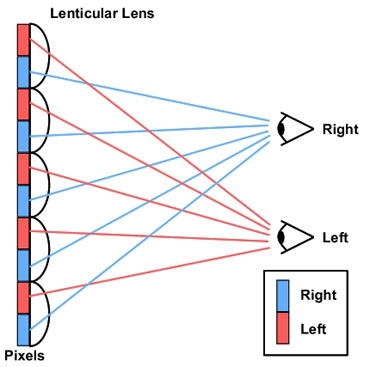

Lenticular lenses

The less popular of the two autostereoscopic models involves the use of lenticules, which are tiny cylindrical plastic lenses. These lenticules are pasted in an array on a transparent sheet, which is then stuck on the display surface of the LCD screen. So when the viewer sees an image, it is magnified by the cylindrical lens.

To see how this works, roll up a newspaper or magazine into a cylindrical shape and hold it up in front of you. Now, with your other hand, cover your left eye. Notice the text and pictures that your right eye can see. Then uncover your left eye and use your hand to obstruct your right eye.

Naturally, given the two varying angles, you will see a bit more of text and pictures on the extreme left side when you look with your left eye, and vice versa. By combining these two images, our brain can perceive depth.

Similarly, when you are looking at the cylindrical image that the TV is now showing you, your left and right eye see two different 2D images, which the brain combines to form one 3D image.

However, lenticular lenses technology is heavily dependent on where you are sitting. It requires a very specific 'sweet spot' for getting the 3D effect, and straying even a bit to either side will make the TV's images seem distorted. Depending on the number of lenticules and the refresh rate of the screen, there can be multiple 'sweet spots'.

...

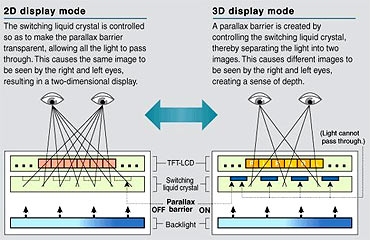

Parallax barrier

The other major method to enable autostereoscopic output is called the parallax barrier. This is being actively pursued by companies such as Sharp and LG, since it is one of the most consumer-friendly technologies and the only one of the lot which allows for regular 2D viewing.

The parallax barrier is a fine grating of liquid crystal placed in front of the screen, with slits in it that correspond to certain columns of pixels of the TFT screen. These positions are carved so as to transmit alternating images to each eye of the viewer, who is again sitting in an optimal 'sweet spot'.

When a slight voltage is applied to the parallax barrier, its slits direct light from each image slightly differently to the left and right eye; again creating an illusion of depth and thus a 3D image in the brain.

The best part about this, though, is that the parallax barrier can be switched on and off with ease (one button on the remote is all it would take, according to Sharp), allowing the TV to be used for 2D or 3D viewing. So on a computer monitor, you could play video games in full 3D glory and then easily switch to 2D mode for your work requirements.

While the wide range of content it offers is heartening, again, the need to sit in the precise 'sweet spots' hampers the usage of this technology.

Still, there are quite a few companies finally looking to make 3D TVs a reality.

Check out: The all new Gadgets and Gaming page!

Comment

article