Novelist Chetan Bhagat's first three books captured the attention and imagination of Young India.

Here was an author from their generation, telling their stories in their language.

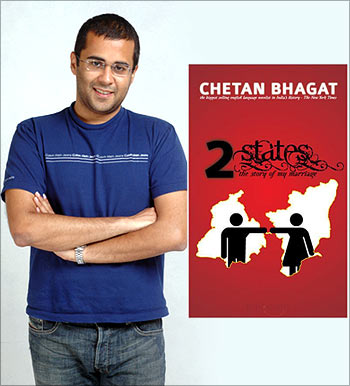

Now Chetan, arguably India's best selling English author, tells us about himself, in the semi-autobiographical 2 States: The Story of My Marriage, which released in India last month.

The book charts the turbulent relationship of a Punjabi boy (Krish) and a Tamil girl (Ananya), IIM-A classmates who fall in love, much to the chagrin of both families.

Below, excerpts from the book's prologue and first chapter.

"Why am I referred here? I don't have a problem," I said.

She didn't react. Just gestured that I remove my shoes and take the couch. She had an office like any other doctor's, minus the smells and cold, dangerous instruments.

She waited for me to talk more. I hesitated and spoke again.

"I'm sure people come here with big, insurmountable problems. Girlfriends dump their boyfriends everyday. Hardly the reason to see a shrink, right? What am I, a psycho?"

"No, I am the psycho. Psychotherapist to be precise. If you don't mind, I prefer that to shrink," she said.

"Sorry," I said.

"It's OK," she said and reclined on her chair. No more than thirty, she seemed young for a shrink, sorry, psychotherapist. Certificates from top US universities adorned the walls like tiger heads in a hunter's home. Yes, another South Indian had conquered the world of academics. Dr Neeta Iyer, Valedictorian, Vassar College.

"I charge five hundred rupees per hour," she said. "Stare at the walls or talk. I'm cool either way."

I had spent twelve minutes, or a hundred bucks, without getting anywhere. I wondered if she would accept a partial payment and let me leave.

"Dr. Iyer..."

"Neeta is fine," she said.

"OK, Neeta, I don't think my problem warrants this. I don't know why Dr Ramachandran sent me here."

She picked my file from her desk. "Let's see. This is Dr. Ram's brief to me -- patient has sleep deprivation, has cut off human contact for a week, refuses to eat, has Google-searched on best ways to commit suicide." She paused and looked at me with raised eyebrows.

"I Google for all sorts of stuff," I mumbled, "don't you?"

"The report says the mere mention of her name, her neighbourhood or any association, like her favourite dish, brings out unpredictable emotions ranging from tears to rage to frustration."

"I had a break-up. What do you expect?" I was irritated.

"Sure, with Ananya who stays in Mylapore. What's her favourite dish? Curd rice?"

I sat up straight. "Don't," I said weakly and felt a lump in my throat. I fought back tears. "Don't," I said again.

"Don't what?" Neeta egged me on, "Minor problem, isn't it?"

"Fuck minor. It's killing me." I stood agitatedly. "Do you South Indians even know what emotions are all about?"

"I'll ignore the racist comment. You can stand and talk, but if it is a long story, take the couch. I want it all," she said.

I broke into tears. "Why did this happen to me?" I sobbed.

She passed me a tissue.

"Where do I begin?" I said and sat gingerly on the couch.

"Where all love stories begin. From when you met her the first time," she said.

She drew the curtains and switched on the air-conditioner. I began to talk and get my money's worth.

Chapter 1

She stood two places ahead of me in the lunch line at the IIMA mess. I checked her out from the corner of my eye, wondering what the big fuss about this South Indian girl was.

Her waist-length hair rippled as she tapped the steel plate with her fingers like a famished refugee. I noticed three black threads on the back of her fair neck. Someone had decided to accessorise in the most academically-oriented B-school in the country.

'Ananya Swaminathan -- best girl in the fresher batch,' seniors had already anointed her on the dorm board. We had only twenty girls in a batch of two hundred. Good-looking ones were rare; girls don't get selected to IIM for their looks. They get in because they can solve mathematical problems faster than 99.9 percent of India's population and crack the CAT. Most IIM girls are above shallow things like make-up, fitting clothes, contact lenses, removal of facial hair, body odour and feminine charm. Girls like Ananya, if and when they arrive by freak chance, become instant pin-ups in our testosterone-charged, estrogen-starved campus.

I imagined Ms Swaminathan had received more male attention in the last week than she had in her entire life. Thus, I assumed she'd be obnoxious and decided to ignore her.

The students inched forward on auto-pilot. The bored kitchen staff couldn't care if they were serving prisoners or future CEOs. They tossed one ladle of yellow stuff after another into places. Of course, Ms Best Girl needed the spotlight.

"That's not rasam. Whatever it is, it's definitely not rasam. And what's that, the dark yellow stuff?"

"Sambhar," the mess worker growled.

"Eew, looks disgusting. How did you make it?" she asked.

'You want or not?' the mess worker said, more interested in wrapping up lunch than discussing recipes.

While our lady decided, the two boys between us banged their plates on the counter. They took the food without editorials about it and I came up right behind her. I stole a sideways glance -- definitely above average. Actually, well above average. In fact, outlier by IIMA standards. She had perfect features, with her eyes, nose, lips and ears the right size and in the right places. That is all it takes to make people beautiful -- normal body parts -- yet why does nature mess it up so many times? Her tiny blue bindi matched her sky-blue and white salwar kameez. She looked like Sridevi's smarter cousin, if there is such a possibility. The mess worker dumped a yellow lump on my plate.

"Excuse me, I'm before him," she said to the mess worker, pinning him down with her large, confident eyes.

"What you want?" the mess worker said in a heavy South Indian accent. "You calling rasam not rasam. You make face when you see my sambhar. I feed hundred people. They no complain."

"And that is why you don't improve. Maybe they should complain," she said.

The mess worker dropped the ladle in the sambhar vessel and threw up his hands. "You want complain? Go to mess manager and complain...see what student coming to these days," the mess worker turned to me, seeking sympathy.

I almost nodded.

She looked at me. "Can you eat this?" she wanted to know. "Try it." I took a spoonful of sambhar. Warm and salty, not gourmet stuff, but edible in a no-choice kind of way. I could eat it for lunch; I had stayed in a hostel for four years.

However, I saw her face, now prettier with a hint of pink. I compared her to the fifty-year-old mess worker. He wore a lungi and had visible grey hair on his chest. When in doubt, the pretty girl is always right.

"It's disgusting," I said.

Excerpted from 2 States: The Story of My Marriage (Rs 95) by Chetan Bhagat, with the permission of publishers Rupa & Co.

Purchase 2 States: The Story of My Marriage online from rediff Books